While researching rare whistles and flutes I came across what may be one of the most rare types of whistles known. These whistles are comparable to what many know as the “shepherd’s whistle”, but also known as an “air-spring” whistle, mouth whistle, oral whistle or Olmec magic whistles.

This type of whistle hasn’t been easy to research, since it has no common name and hasn’t been studied much. A similar type of whistle is still commonly used today among who use dogs to herd animals such as sheep. This contemporary use as a herder’s whistle is why it’s easier to find this kind of whistle when you search “shepherd’s whistle” in google than with any other of the names.

There have only been a few research papers on this type of whistle in pre-Columbian cultures, and I have found even fewer studies of the contemporary version known as the Shepherd’s whistle. One of the best I have found can be downloaded above or viewed with the link below.

https://www.academia.edu/31291165/Silbatos_bucales_de_la_Mixteca

The research paper above is written by Gonzalo Sanchez who studies ethnomusicology, and is a specialist in Mesoamerican instruments. This paper outlines Sanchez’ study of these enigmatic sound making devices in pre-Columbian cultures, and a few different variations of these noise devices from that region. There are a few other papers out there that discuss these “mouth” whistles, but few and far between. It seems this type of whistle has been overlooked by researchers in the field of ethnomusicology, which has been a disappointment.

Contemporary Counterpart

These ancient mesoamerican whistles are very similar to the commonly used contemporary counterpart known as shepherd’s whistles. Shepherd’s whistles are used to communicate with herding dogs over long distances in the present time. You can find these made of stone, wood, plastic, and metal; in a variety of similar designs. Mainly sold as tools for communicating with herding dogs in the field, they can also be found sold as gifts and toys. The Greenstone (Jade like stone) version below, from New Zealand, is a fine example of a contemporary mouth whistle.

This Greenstone whistle design is popular due to its durability, sharp tone, clear pitch, and range of sounds and its appearance. It doesn’t bend like metal or plastic whistles. This whistle can be heard clearly and for several hundred meters, and those who feel connected to the outdoors wear the whistle as a pendant. Greenstone from Hokitika area, West Coast, New Zealand. Colouring can vary slightly due to the characteristics of stone.

As you can see, there are many similarities between the ancient mesoamerican mouth whistles (air-spring or oral whistle), and the contemporary shepherd’s whistle. You can find these for sale online with prices anywhere from $10-$200 each. Just search “shepherd’s whistle” online, and check out all of the results. Though finding any studies on these whistles have come up short on my end.

Olmec Magic Whistle

Roberto Velázquez Cabrera is a researcher who has studied the ancient Mesoamerican counterparts to the contemporary shepherd’s whistle for many years. I have found quite a few of his articles which detail findings about these enigmatic whistles.

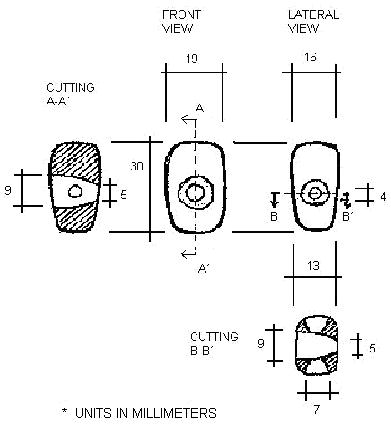

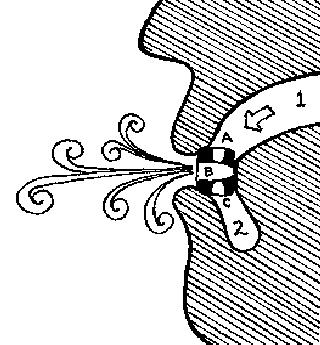

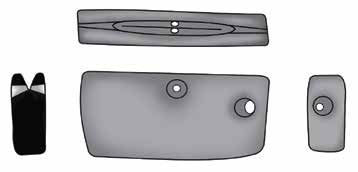

The Olmec style of the mouth whistle vary in design from the other versions found, but are used in the same manner. Some of Mr. Cabrera’s research included the diagrams below showing some of the measurements and the method of playing these mouth whistles.

http://www.geocities.ws/rvelaz.geo/bstone/smagici.html

http://www.geocities.ws/rvelaz.geo/bstone/bstone.html

This Olmec mouth whistle (silbatos bucales) is around 3,000 years old. Some of the researchers such as Roberto Velazquez estimates that many of the artifacts for these whistles are probably not categorized properly in the museum collections around the world, and often overlooked.

Roberto Velazquez writes in one of his articles about finding this unique black stone mouth whistle and his perspective on the progress of developing these ancient artifacts. He studies this ancient instrument with recordings and experiments with playing techniques. Velazquez calls these instruments “aerophones of spring of air” or “Mexican noise generators “, since their sound producing behavior is unique among most aerophones, like popular whistles and flutes. His research has been vital in the development of this article.

During his research Mr. Velazquez created replicas of many of the artifacts he studied. Some of these replicas are shown in the images above.

Mr. Velazquez points out a similar representation of these noise generators in one of the Aztec codex books. On this page it shows various other instruments such as teponaztli and huehuetl drums, conch shell trumpet and flutes, so he estimates that the image on the top left is one of these noise generators, and must be important if placed on this page of other important tools and instruments.

Some of the research about these whistles show variations of these devices created in Spain from broken pottery shards. The ancient creators of these whistles used broken pottery to create the mouth whistles they used, which shows the ingenuity and resourcefulness of ancient peoples.

Recreating Replicas of Mouth Whistles

All this research led to me recreating some replicas of these artifacts to experiment with myself. Utilizing my skill in carving softer stone (such as soapstone and pipestone) I proceeded to start work. It took me no time at all to create a replica that seemed to work, based on the designs of previously studied artifacts. Experimenting with shapes, sound hole sizes and splitting edge angles, I determined that these devices could produce a wide range of tones.

During the process I created multiple versions of these mouth whistles, some of them easier to play than others. Some of my findings show that the person using these whistles could easily replicate many natural sounds related to song bird, wind sounds or loud whistles, depending on the devices design.

The biggest factors were the size and angle of the sound holes. Differing the sizes of the holes on each side slightly could affect the overall pitch greatly from side to side, but if the contrast was too great no sound could be produced. The players ability to maneuver their tongue in various positions under the whistle was extremely important for tonal changes, and determining how loud the sounds were.

Basically you are creating an ocarina (vessel flute) within your mouth, giving you the ability to change the tone easily and without the use of your hands, like traditional ocarinas and flutes. Considering all of these factors, I assume these devices were simple yet effective tools for communication over long distances and mimicking animals and natural sounds for hunting and other reasons.

While playing these replicas outside, some of them got the attention of song birds visiting our winter feeder, they seemed very interested in this human who made bird like sounds like them.

References:

- http://www.geocities.ws/rvelaz.geo/bstone/bstone.html

- http://www.geocities.ws/rvelaz.geo/bstone/smagici.html

- https://www.academia.edu/31291165/Silbatos_bucales_de_la_Mixteca

- https://arqueologiamexicana.mx/mexico-antiguo/los-silbatos-bucales-de-la-mixteca-instrumentos-multifuncionales

- https://www.arrowtownstonework.co.nz/jadeshop/shepherdswhistle

- https://unam.academia.edu/GonzaloSanchezS

- https://www.mexicolore.co.uk/aztecs/music/death-whistle

- http://www.geocities.ws/rvelaz.geo/english.html

- https://independent.academia.edu/RobertoVel%C3%A1zquezCabrera

- https://www.danzasmexicanas.com/sonidos-mexicanos/roberto-velazquez